Convening a national seed gathering to move towards greater seed sovereignty for Scotland

Seeds are the starting point for almost all the vegetables we eat, and in terms of food sovereignty, seeds (next after land) are the most powerful resource we need to keep within our control. In Scotland at the moment, this isn’t the case – but we believe it could be just within our grasp.

Using the money we raised in our recent crowdfunding campaign Common Good Food will hold a seed saving gathering this November to bring growers and movers from across Scotland to see how we can collectively build up and share this most essential resource for people-powered food growing.

As a starting point, perhaps something we need to ask is:

What is our vision for seed sovereignty in Scotland?

First, some background:

First, some background:

There is currently no commercial vegetable seed grower in Scotland - so at the moment, if you are a market or hobby gardener wanting to get varieties to do well, your best bet for getting hold of seeds is to head to a wholesale supplier in Wales, England or Ireland.

The reason for the dearth of commercial suppliers is enigmatic. There are hundreds of varieties of vegetables that do well in Scotland, including a whole rake of native Scottish ones, and there appear to be plenty of people growing vegetables too. Just how much demand there is for vegetable seed in Scotland is not clear, but the background picture of what Fife Diet’s Mike Small has called Scotland’s Local Food Revolution would seem to back a rapid increase in individuals wanting more local vegetables - and anecdotal evidence from eight years at Fife Diet suggests that many individuals and community groups across Scotland are desperate to get hold of Scottish seeds.

On a UK level, there has certainly been a boom in demand for vegetable seeds. According to sales figures from Suttons in an article by the BBC in 2009, vegetable seed sales for home gardening increased rapidly from 40% in 2005 to 70% in 2009. Meanwhile at the Real Seed Catalogue in Pembrokeshire in Wales, business is booming. This January and February they were having to cap their orders each week as the demand was greater than what they could supply. With a similar wet climate to parts of Scotland, and an amazing collection, they are currently one of the best places to go for seeds for Scotland - and they are keen promoters of seed saving.

In the commercial sector, the Scottish Government Agricultural Census for 2014 has shown that the total area of land in vegetable production increased by 1,700 hectares (16%) between 2003 and 2008 (mostly due to increases in peas and carrots) followed by an average step increase of 2-3% (360 hectares) annually since then. Interestingly, agricultural seed supplier Elsoms, who source most of their seeds from Dutch seed breeders Bejo Zaden, are currently advertising for a vegetable seed specialist to be based in Scotland and Northern England They say that “Working as part of the vegetable team the key objective is to build on our existing success in this region by increasing sales from our expanding portfolio”

So it certainly would seem after that there could be an economic case for establishing better Scottish seed supply – but what is the case for food sovereignty?

Perhaps part of the challenge of growing vegetables in Scotland is not that the climate is particularly challenging, but that most varieties are grown and bred in the sunny dry climate of southern England (where it is easier to get a commercial seed crop) – and that hardly anyone is breeding vegetables for small scale production. Ken Cox and Caroline Beaton, authors of Fruit and Vegetables for Scotland (2012), were motivated to write the book largely because there is such a lack of information on growing in Scotland. They say that most of the large seed suppliers have “no knowledge of Scottish conditions, no trialling done in Scotland, and no appreciation of the different conditions we garden under. As far as we can ascertain, only the Beechgrove Garden and Gardening Which? Run vegetable trials in Scotland”.

Various studies have shown that seed adapted to local conditions can give better results than mainstream varieties, especially for low input organic systems and marginal land – especially when combined with participatory breeding programmes:

“To meet the needs of these [organic and low-external-input] systems, breeding programs must decentralize selection, and although decentralized selection can be done in formal breeding programs, it is more efficient to involve farmers in the selection and testing of early generation materials. Breeding within these target systems is challenging, both genetically and logistically, but can identify varieties that are adapted to farming systems in marginal environments or that use very few external inputs.”

The above, from a study from the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences in Washington University has a good review of research done on this subject.

Furthermore, as climate change begins to affect our growing season more and more, breeding of Scotland-specific varieties will become increasingly imperative.

Scottish Seed Sovereignty

I have a hunch that we are most of the way there, which is why I am excited by the potential of our National Seed Gathering in November.

Although there is no dedicated seed supplier, there are plenty of suppliers of good quality fruit plants and trees - and most food plants that are propogated by cuttings rather than by seed. We are for example famous for our seed potatoes, which reached a record level of production last year.

Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA) not only hold a gene bank of all the potato varieties of Scotland, they also hold a collection of over 9,000 accessions of vegetable seeds covering 27 vegetable crops - in Broad Bean alone they have over 200 different varieties. These however are stored at -22ºC and aren’t grown every year, or made available to the general public.

There are also significant groups of people who are breeding and saving their own seeds across Scotland. The crofters of Shetland have been keeping their specific seeds and breeds going for hundreds of years, including the Shetland Cabbage and other varieties. Just this March, a new Shetland Seed Library started up. Meanwhile in Orkney, the traditional Bere, a variant of barley, is being ground into meal every year by Barony Mill. In the Uists, the crofters there grow Bere, Small Oats and Hebridean Rye. In South Lanarkshire, East Kilbride Development Trust have been developing new varieties for a number of years, in the Borders baker Andrew Whitley is developing a new variety of Scottish bread wheat, and seed saving is being taught on the Curriculum for Excellence by the Soil Association's Crofting Connections project. There are also many individual growers all across the country saving their own seed and developing their own varieties.

National Seed Gathering this November

The gathering as yet does not have a venue or date, but it will be held in Edinburgh or Glasgow at the end of November (to allow time for people to gather seeds to bring to the conference).

We hope to attract about 150 people to the event, and we will use collaborative methods to collectively decide how to progress. Here are some questions I think we need to ask:

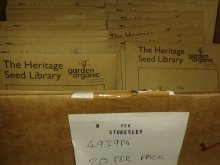

- How do we set up a national collection which houses a the best varieties for Scotland’s varied microclimates, as a counterpart to the excellent Heritage Seed Library at Garden Organic in Warwickshire?

- Can we set up a network of seed savers across the country that will allow individual growers to improve and develop varieties for their area?

- How can we encourage more growers to save their own seed and take an interest in the rich living heritage of Scottish seeds?

If you would like to be involved, please get in touch with us on [email protected]. Or stay up to date with plans for the conference by signing up to our mailing list here. Please share this article widely!